The Web Pubs

Sunset Creek

by C M Nelson

Reflections

by Jay Miller

The Paper Pubs

Prelim. Report

Sunset Creek

Eratta

Culture Change

Solland Thesis

Supplements

Correspondence

Level bag tools

2014 Drawdown

Proj. Points

Setting

Excavatiions

Field Profiles

Features

Camp Life

Ranching

remains

45KT26

Catalogs

Primary Catalog

Nos 1-400

Nos 401-4813

ID Bone

Level Totals

Artifacts by

level

Artifact

comp catalog

Level Bag

Artifacts

Relationship between the Cayuse Phaseand the Ethnographic PatternINTRODUCTION |

|||

|

[50] Since the basic patterns established at the beginning of the Cayuse Phase persist until the termination of the archaeological record sometime in the middle of the nineteenth century, it is obvious that there must be some direct relationships between ethnographic patterns of Plateau culture and the archaeological manifestations of the Cayuse Phase. This discussion seeks to define that interrelationship, a necessary step towards understanding both the origin of the Cayuse Phase and [50/51] the antiquity of ethnographic Plateau culture. If it is found that there is a necessary connection between the primary characteristics of the Cayuse Phase and ethnographic cultural patterns, that the two are synonymous phenomena, then an explanation for their origin must be sought in the factors surrounding the emergence of the Cayuse Phase. But first the ethnographic pattern must be described. This will be done primarily in terms of settlement patterns and economic organization, phenomena which can be tested for in the archaeological record with relative ease. THE ETHNOGRAPHIC PATTERNEthnographically, population was concentrated much of the year in winter villages situated in the deep valleys at the margin of the Columbia Plateau (Anastasio 1955). The winter villages, which were occupied for approximately five months a year, formed the basis for social units larger than the family and geographically dominated the yearly economic cycle which was designed to supply enough surplus food to support a sedentary existence during the winter months. They were situated along trunk streams and their larger tributaries, and occasionally along the shores of lakes. The specific locations of winter villages were determined by elevation and topography producing favorable climatic conditions, the presence of winter food resources necessary to supplement surpluses of roots and fish, and proximity to food resources customarily utilized in the early spring and late fall. |

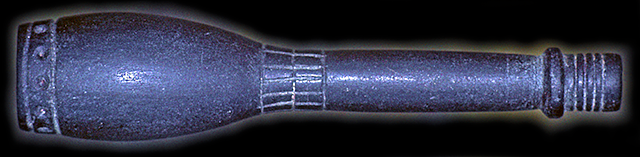

Conventions Abstract Table of Contents Letters Figures & Tables Acknowledgements Introduction Definitions Setting Cultural Record Introduction Vantage Phase Cold Springs Frenchman Spring Quilomene Bar Cayuse Phase Characteristics Age Ethnography  Salishan Stratigraphy Cayuse I Cayuse II Cayuse III Discussion Summation Models for Prehistory Typology Stone Artifacts Flaked Stone Percussion Ground Stone Bone/Antler Tools Shell Artifacts Metal Artifacts Raw Materials Methodology Rockshelters References Cited |

||

|

Although the size and position of winter villages, and the details of land utilization varied with local differences in climate and topography, the geographic distribution of food resources, and the yearly variation in the abundance of these resources (see Anastasio 1955), the general character of the yearly economic cycle is illustrated well by Ray's (1932) description of the Sanpoil and Nespelem, a group located on the northern edge of the Columbia Plateau that was affected less by the protohistoric intrusion of horse culture than surrounding groups. According to Ray (1932:27-29), the yearly cycle of these people began early in the spring when the winter villages were abandoned for nearby, temporary camps. In the protohistoric period each village contained a number of pit houses, a structural form which was replaced by mat houses that were built almost entirely above ground. Like the winter villages, the temporary spring camps were always set up along the Columbia River. They were occupied for about three weeks during which the men hunted fowl and rabbits, and gathered freshwater mussels, while the women dug early-appearing roots in the vicinity of the river. This period was followed by a gradual removal to the root digging grounds south of the Columbia. Here small bands, each of a few families, set up temporary camps. The women were constantly occupied with digging and drying roots. For the most part, the men loafed about the camp, gambling and gossiping. Rabbits or antelope were hunted occasionally. During this period the old, ill, and crippled were left along the river, where they were cared for by a few of the able bodied who had remained behind for that purpose. The summer fishing season began in early May and lasted until the first of September. During this period, salmon were taken in traps operated in streams tributary to the Columbia River. In the fall people dispersed from these camps, traveling as they desired either to the mountains north of the Columbia to gather fall roots and berries and to hunt, or to the fall fisheries along the banks of the Columbia. Those who had traveled to the mountains returned to these fisheries where salmon were taken in seines or speared from canoes. By far the greater number of fish, it should be added, were taken with the trap method during the summer season. [51] [52] The winter villages were reoccupied in mid-October. Underground pit houses were cleared out or excavated, while roots and dried salmon were placed in permanent storage. Such villages contained 20 to 300 individuals, and averaged a population of 50 or fewer. Villages of 100 to 150 were not uncommon during the early historic period, but may have been a result of the protohistoric intrusion of horse culture. The specific composition of villages varied from year to year as families changed their residence in response to their own economic and social needs. Although the details of Ray's description of the Sanpoil and Nespelem do not apply to all groups of Plateau Indians, the basic land and resource utilization patterns inherent in the description embody an economic system common to groups throughout the Columbia Plateau prior to the protohistoric influence of Plains culture (see Anastasio 1955; Ray 1939). The basic characteristics of this system are the winter village pattern of settlement and the maintenance of winter villages predominantly through root gathering, salmon fishing, and winter hunting. The relative importance of each of these major food resources varied with its local abundance and its seasonal supply, but each was necessary to the maintenance of the winter village pattern from year to year. TANGIBLE TRACES OF THE ETHNOGRAPHIC PATTERN IN THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORDIntroduction. What tangible traces would the establishment and year to year maintenance of winter villages leave for archaeologists to find? What is the distribution of such evidence in the archaeological record? Documented below, the answers to these questions indicate that the appearance of the Cayuse Phase marks the emergence of the ethnographic patterns of Plateau culture. The Characteristics of Winter Villages. Although most Plateau ethnographers have tended to stress the role of the village in political and social organization, the following features of the village itself emerge from an examination of the work of such analysts as Ray (1932; 1936; 1939), Anastasio (1955), and Walker (n.d.). Viz: Deward E. Walker: (1966) "A Nez Perce Ethnographic Observation of Archaeological Significance." American Antiquity, 31(3):436-437; (1967) "Mutual Cross-Utilization of Economic Resources in the Plateau: An Example from Aboriginal Nez Perce Fishing Practices." Washington State University, Laboratory of Anthropology, Report of Investigations, No. 41; (1967) "Acculturative Stages in the Plateau Culture Area." 66th Annual Meeting of the Idaho Historical Society. Boise. 1. Population tended to be dispersed in small units during the summer and concentrated in villages during the winter. However, high population concentrations occurred sporadically at other times of the year in areas where exceptionally large food supplies naturally occurred. These included natural fisheries such as Celilo Falls and Kettle Falls, and extremely productive root gathering grounds. Such local concentrations of population, common in the historic period, were made possible by the protohistoric introduction of the horse, a means of transportation which allowed food and people to be massed in far higher densities than was possible during prehistoric times. It is therefore highly improbable that local population densities during the fully prehistoric period ever reached those characteristic of the historic and protohistoric periods. Nevertheless, it cannot be doubted that the population was higher and denser at sites where natural resources were particularly abundant. The same reasoning can be applied to winter villages, many of which contained hundreds of people during the historic period. Such large villages were undoubtedly a result of the ability, made possible by the horse, to concentrate the huge surpluses of roots and fish necessary to support the high local population densities produced by large villages. As is noted in the discussion of the Cayuse III Subphase, archaeological evidence for such large villages first appears in the protohistoric period and is evidently correlated with the introduction of the horse. Prior to the protohistoric period, population must have been concentrated in relatively small winter villages during the winter months and dispersed over the adjacent territory during the rest of the year, when surpluses were being accumulated for the following winter season. The concentration of population at root gathering grounds was probably infrequent due to difficulties in [52/53] transporting large surpluses over great distances, but concentrations of local population at particularly productive fishing sites almost certainly must have occurred. This agrees well with the archaeological evidence, for large sites tend to be highly concentrated in valleys where winter villages and fishing sites are ethnographically reported. 2. An obvious feature of winter villages is the construction and maintenance of semi-permanent dwellings. Such dwellings might be semi-subterranean earth lodges, large mat lodges constructed over very shallow pits, or intermediate forms combining fairly deep pits with mat-covered superstructures. The remains of such structures are common features of Cayuse Phase components. They tend to occur in groups as parts of site complexes and are distributed in areas where winter villages were traditionally established. 3. Ethnographic evidence (e.g., Ray 1939; Walker n.d.; Schwede 1966) demonstrates that villages were named, that they were situated in finite geographic localities, and that village membership and rights in the resources intimately associated with villages were allocated in the framework of the kinship system. Like the practice of maintaining semi-permanent dwellings, these features imply village stability through time, a feature which is characteristic of numerous sites and site complexes during the Cayuse Phase. Village stability is also one of the factors which tends to produce complexes of related sites centered around the winter village. 4. Associated burial areas are a natural outcome of the establishment and year to year maintenance of a winter village. This follows from the stability of the village, the long period of occupancy each year, the concentration of population at the village site, and the tendency for a higher death rate during periods of winter hardship. Thus the establishment and maintenance of winter villages explains the basic characteristic of Cayuse Phase site complexes, the association of large open sites, burial areas and house remains. 5. Since the maintenance of a winter village requires the storage of food surpluses, equipment, and the mats and structural members of dwellings, the association of storage shelters and storage pits with Cayuse Phase site complexes is a feature which is easily explained. Such associations are not inevitable, however, since elevated platforms were also widely utilized for storage (Ray 1942:180). 6. Since the winter village geographically dominates the yearly economic round and is the primary site of many important social and religious activities, it is characterized by a nearly complete technological inventory. This is reflected by the highly varied assemblages of artifacts typically associated with sites of any Cayuse Phase site complex. 7. Since winter was one of the most important hunting periods, hunting gear and the faunal remains of deer and elk are well represented at the winter village site. This too is a regular feature of the Cayuse Phase site complex. Recently the interrelationships between known village areas and recent Cayuse Phase site complexes have been reviewed in some detail for a small section of Nez Perce territory (Nelson and Rice 1966: Appendix A). It was found (1) that archaeologically obvious site complexes did not always correlate precisely with ethnographically reported village areas, and (2) that archaeologically verifiable village areas almost invariably contained the basic elements of the Cayuse Phase site complex. This led to the conclusion that there was a direct relationship between the winter village pattern and the Cayuse Phase pattern of site complexes even though specific village areas were very difficult to infer from the archaeological data itself. [53] [54] Relationship between the Ethnographic Pattern and the Cayuse Phase. The age, distribution, and density of house remains and site complexes, and the material culture and faunal remains typically associated with site complexes, indicate that the Cayuse Phase embodies the ethnographic cultural patterns of the Columbia Plateau. Moreover, since site complexes of the type associated with the winter village pattern first appear at the beginning of the Cayuse Phase, the emergence of ethnographic Plateau culture must date from the emergence of the Cayuse Phase. [54] LAST REVISED: 13 JAN 2016 |